We sat down to discuss the opioid epidemic with an expert, Dr. Andrew Herring, Attending Emergency Physician, Associate Director of Research, and Medical Director of Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System’s substance use disorder treatment program. It’s an especially urgent issue, with a recent report sharing a grim reality: last year alone, 93,000 Americans died of an opioid overdose, a 29 percent increase over 2019. Dr. Herring walked us through the scope and scale of the challenge our nation is facing.

Anyone who has ever read the news knows the opioid crisis is a genuine epidemic in the US. Can you take us back a bit in time and give us the context?

At a high level, we’re living out a worst-case scenario here with a substance that has touched every kind of person — from children to young adults to the elderly — in urban areas, rural parts of the country, suburbs, everywhere. In contrast, prior to this, heroin was our biggest problem and while tragic and filled with human suffering, overdose rates were still relatively low and the impact was focused in urban areas.

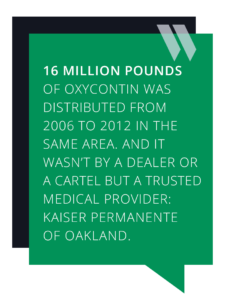

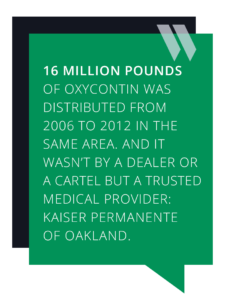

In 1993, for example, The New York Times published a story on the biggest heroin bust ever at the time: more than a thousand pounds of heroin in Oakland. At that time, that was an incredible amount. Now if we fast forward less than a decade later, 16 million pounds of opioid analgesic was distributed from 2006 to 2012 in the same area. And it wasn’t by a dealer or a cartel but trusted medical providers. Including emergency physicians like me. That number is astounding but that was actually a relatively low-exposure county. Other places in America were much, much worse.

How did it even get to that point? That’s a mindblowing amount — and it’s just one of many affected areas in America.

The late 90s through the early 2000s saw the corporatization of medicine really take hold — and the system got a lot more efficient. Opioids entered at a moment when it was possible to make this really connected effort to get them into every corner of the market — from the Florida Everglades to fishing towns in Alaska — and succeed.

It was a movement with a lot of players — from big pharmaceutical companies to hospitals and clinics to distributors and pharmacists. Certainly there entities that clearly made breathtaking profit from it and others, like hospitals, may have indirectly benefited from it through, for instance, increased patient satisfaction scores. And there were many in the medical community who believed the positioning — that oxycodone was good pain management, that people shouldn’t suffer, and there was no risk of addiction — and that they were doing the right thing by prescribing it to patients.

But we understand now very clearly how dangerous opioids are.

Yes, we certainly do. Chemically, oxycodone is in many ways indistinguishable from heroin. With heroin, people using it intend to get high; that’s what the purpose is. With oxycodone, the pharmaceutical industry wrapped it in medical language, making it about pain relief, so people thought they needed to take more to get ahead of their pain. And eventually, they’d realize “Whoa, I really like this” but it’s hard to admit you may have a dependency. The stigma is very real.

What happened once the danger became broadly understood?

By 2005, the number of deaths and the trillions of pills that had been prescribed was just so outrageous, it really couldn’t go unaddressed any longer. It was just so out of step with the rest of the world but pharma fought back any attempts to regulate it. That’s why they should pay so dearly; they truly delayed common-sense regulation that would have saved lives. But by 2012, the prevailing sentiment was, enough. We then saw a massive cascade of regulatory events that targeted physicians and pharmacists. In some ways, this was a worst-case scenario because millions of people were exposed and then rapidly abandoned.

That sounds like a good thing on the surface. Can you share more about the unintended consequences of these good intentions?

When you cut off supply, the demand is still there. And unfortunately, it led to the emergence of the largest illicit opioid market in the history of mankind. The cartels went corporate; they became organized, built distribution networks and production operations, and stepped in to fill the void.

For them, it made sense. Heroin is like the craft beer of drugs — expensive to produce, limited, you have to rely on farmers to grow and harvest poppies, etc, etc. But opioids can be produced cheaply and quickly — and now they had a much, much bigger market: customers not just in urban areas but all over the United States. So they started making and selling fentanyl. When you have fentanyl enter the consumption pattern, people die at higher rates — it’s hard to know how weak or strong it is when you take it. It works so quickly that it’s very easy to overdose.

We’re still very much in the thick of dealing with fentanyl — in fact, the fentanyl market really took off on the West Coast relatively recently with the advent of the pandemic.

How do we help those people?

Helping people with opioid use disorder and chronic pain is expensive and very time consuming but it can be done. And it’s worth it — these are human beings. It means a combination of working with pharmacology to rotate people to non-opioid ways of addressing pain and less harmful opioids like buprenorphine, working with psychological factors that make them vulnerable to relapse, etc. And if chronic pain is a factor, it also means adding in elements like movement and touch to address that issue.

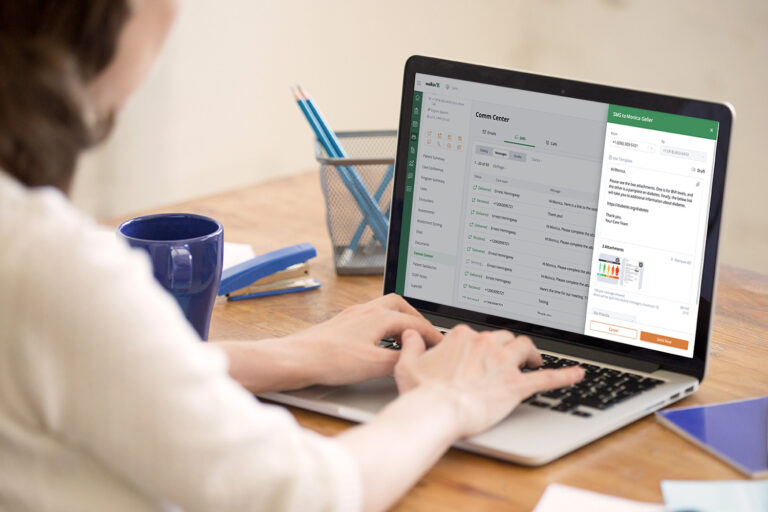

I’m an attending ER physician and the medical director of Highland Hospital’s substance use disorder treatment program. We’re using patient navigators who function as coaches and are trained to be part of the system to be part of the process, offering non-judgmental support to provide harm reduction and prevention. We’re actually using Welkin technology to effectively help navigators keep track of where patients are — and for us to ensure we’re all on the same page as we work through helping each patient. That’s critical with this patient population; it’s very challenging to help them work through dependency and we’re using this technology to alert patient navigators when there are immediate issues that need to be addressed. Overcoming opioid addiction is not a linear path. Welkin helps our teams ensure all our patients are getting the right level of care.